How the Lamp Light of Peace can benefit animals in need today.

We have teamed up with the The War Horse Memorial CIC, who seven year’s ago unveiled in Ascot, Berkshire, the first national memorial dedicated to the millions of UK, Commonwealth and Allied horses, mules and donkeys lost during The Great War and subsequent conflicts.

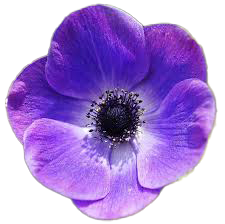

Poppy, named by the country’s guides and brownies in a national competition, is a larger than life bronze horse and stands on a three metre high stone plinth created by acclaimed British sculptor Susan Leyland. It has become much more than a memorial. It has created an opportunity to raise funds for struggling animal charities and welfare organisations through the memory of those fallen victims of war and the emblem of a purple poppy to be worn alongside the red.

War Horse Memorial CIC, sells purple poppy pin badges and knitted purple poppies for treasured pets to wear ahead of International War Animal Day, on February 24 and on November 11 when we remember ALL lives lost in Two World Wars and conflicts that followed, through The Animal Purple Poppy Fund.

As Co-Founder of this organisation, we are working with others in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and America to create an animal memorial in France dedicated to those animals who went to war and never returned, and will use some of the money raised from Lamp Light of Peace sales to help make that happen.

For more information on The War Horse Memorial and the Animal Purple Poppy Fund:

The Lamp Light of Peace will support animal charities with £5 from every sale of each Lamp.

Your pets can join in

In remembrance day celebrations

War, and its consequencies is naturally viewed from a human perspective. However, it is only right we also remember the contribution of animals in both World Wars and subsequent conflicts. Tens of millions of horses, donkeys, dogs, cats and pigeons gave service during those dark years - and sadly, many never returned.

For example, the role that dogs played can never been underestimated. Up to 20,000 dogs of different breeds and sizes were trained for front-line duties during World War One. Dogs like Woody (pictured below) took messages between the lines and sniffed out enemy soldiers. Their roles were deemed so important that in the early months of 1917 the War Office formed the War Dog School of Instruction in Hampshire to train them. They were also used for pulling machine guns and equipment. Many - about 7,000 - had been family pets, while others were recruited from dogs' homes or came from police forces.

Sentinel dogs were trained to stand quietly on the top of the trench alongside their master's gun barrel, in order to let the soldiers know if anyone attempted to approach the barbed wire.

The picture (below), courtesy of The Imperial War Museum, shows French Red Cross dogs, including Labradors like Woody, line up for inspection on the Western Front, in 1914.

These specially trained dogs wore harnesses containing medical equipment, which they delivered to injured soldiers on the battlefield.

The skills, loyalty and devotion of our canine friends was called on again in World War Two. British forces utilized various dog breeds for a range of crucial roles, including sentry work, mine detection, messenger duties, and even as companions. German Shepherds, Doberman Pinschers, Labradors, and Airedales were among the breeds favoured for their specific skills and temperaments.

Some were were specifically trained to locate and detect landmines, playing a vital role in breaching minefields, and others were used for search and rescue, locating people buried under rubble, and even laying telephone wires.

Millions of animals were taken from family homes and farms to aid allied forces during both World Wars, so it is only fitting that those of us with much loved pets, should be encouraged to light a Lamp Light of Peace at 10.57am on 11th November, 2026, to 'shine a light' on the animals who also served, and for the lamp to be re-lit for years to come.

Meet Patrick. He's a miniature Shetland pony, with a lovely temperament and a kind are caring nature. He is something of a celebrity and is the current Mayor of Cockington, a beautiful village in South West Devon. He has been trained as a therapy pony, which means that his calming effect can help alleviate pain, reduce stress, anxiety and improve overall psychological state in people young and old.

However, if Patrick had lived during either world wars his fate would have been very different. A war horse is often thought of as a huge cavalry charger or a smart officer’s mount. But during the First World War the roles of equids was much more varied. A Shetland pony like Patrick can pull twice their own weight, and because they evolved in harsh environments, are known for their sure-footedness.

The Army needed thousands of civilian horses to serve alongside its soldiers. Different types were suited to different military roles. Riding horses were used in the cavalry and as officers’ mounts. Draught horses switched from pulling buses to hauling heavy artillery guns or supply wagons. Small but strong multi-purpose horses and ponies carried shells and ammunition. Without these hard-working animals, the Army could not have functioned.

By 1917, the Army employed over 368,000 horses on the

Western Front. The vast majority of these were draught or pack animals rather than cavalry horses. Thousands succumbed to fatigue or diseases like mange. Others fell victim to the weapons of modern war. The use of gas, artillery, mines, machine guns, mortars and tanks made the front a terrifying place for horses. In the early days of gas warfare, nose plugs were improvised for horses to help them survive. Later, special types of horse gas masks were developed.

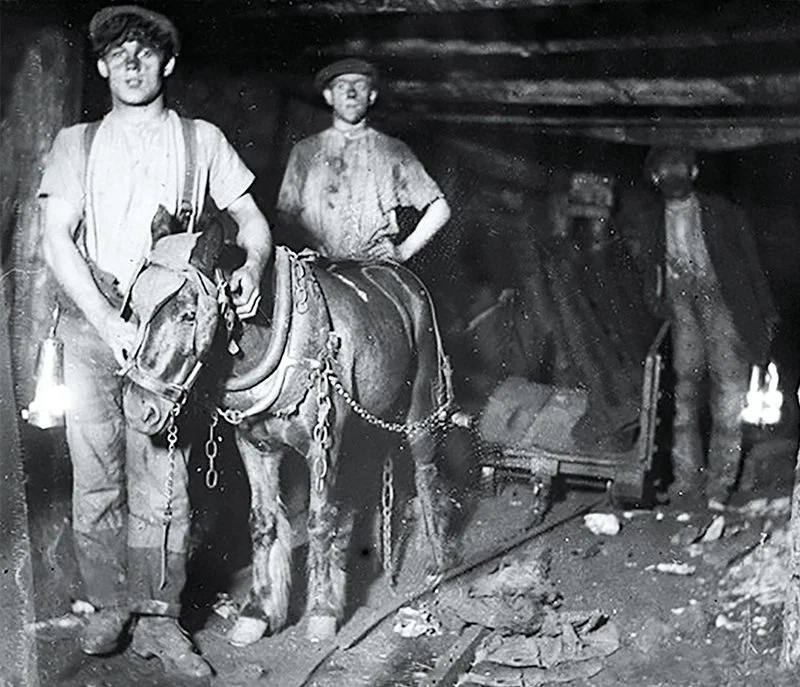

Back home, one of the most significant uses of animals was in the coal mines. Pit ponies, small horses or ponies used underground, played a crucial role in the mining industry, hauling coal from the depths of the earth to the surface. With many horses requisitioned for the war, the demand for pit ponies increased.

These ponies worked in harsh conditions, often spending their entire lives underground. Despite the challenging environment, they ensured a steady supply of coal, essential for powering factories, railways, and ships.